By H.E. Metropolitan Cleopas of Sweden

From antiquity to the present day, humanity has sought ways to express truth, to teach virtue, and to demonstrate the consequences of human behavior.

Two great pedagogical currents of history—seemingly different yet essentially convergent—are the fables of Aesop and the teaching of Christ, as interpreted and lived within the Orthodox Tradition.

The human journey toward truth has never been instantaneous; it has been gradual, pedagogical, and revelatory. Even before the word of the Gospel was heard, humanity had already received seeds of truth through conscience, experience, and observation of the world.

Within this process belong the fables of Aesop, which, although lacking a revelatory character, vividly depict the natural moral order.

With the coming of Jesus Christ, this moral knowledge is not abolished but transcended and brought to its fullness.

The Fathers of the Church, with discernment and wisdom, recognized in these fables a preparation for the Gospel—a vestibule that prepares humanity for the truth of salvation.

The educational history of humanity neither begins nor ends with Christianity, yet in Christianity it finds its fullness and its salvific completion.

Before the Gospel, humanity was instructed through experience, philosophy, and myth. One of the most significant bearers of this moral preparation was Aesop, whose fables, in a simple yet penetrating manner, highlighted timeless truths about human nature.

Aesop’s fables employ simple images—animals and everyday situations—to convey profound moral teachings. In a similar manner, Christ spoke to the people through parables: the Sower, the Prodigal Son, the Good Samaritan. In both cases, truth is not imposed; it is revealed to the listener who is prepared to reflect.

As Saint John Chrysostom notes, the parable brings lofty meanings down to the measure of human weakness, so that teaching may become comprehensible and experiential:

“Through parables He educates, so that they may receive the truth not by compulsion, but by free choice” (Homily XLV on Matthew, PG 57, 464).

The same pedagogical logic is evident in the fables, which function as a mirror of human behavior.

When Christ came “in the fullness of time,” He did not abolish natural moral knowledge, but transcended and perfected it, leading it from the level of behavior to the level of salvation and communion with God.

Aesop’s fables function pedagogically: they present condensed narratives with symbolic figures that culminate in a clear moral conclusion. They act as a mirror of human behavior, provoking self-knowledge.

Correspondingly, Christ used parables as a means of revealing the Kingdom of God.

Saint John Chrysostom, interpreting the parables, emphasizes: “For He does not speak in parables out of obscurity, but out of condescension, so that He may lead us from sensible things to intelligible ones” (Homily XLV on Matthew, PG 57, 464).

The Church recognizes that image and example are indispensable for the transmission of truth, especially in a spiritually immature world. Therefore, Aesop’s fables are examined as a preparation for the Gospel and interpreted in the light of the Fathers of the Orthodox Eastern Church.

Myth and Parable as Pedagogical Forms of Discourse

Examples of Fables and Theological Correspondences

Myth, like parable, functions as indirect speech. It does not impose truth but suggests it. Christ’s parabolic teaching fits precisely within this pedagogical framework.

Saint John Chrysostom emphasizes that parables do not aim at obscuring the truth, but at condescension to human weakness (Homily XLV on Matthew, PG 57, 464).

Human beings are called to recognize themselves within the narrative. The same occurs with Aesop’s fables, which render the listener both judge and, simultaneously, accused of their own behavior.

a) The Hare and the Tortoise – Patience and Humility

The fable highlights the superiority of steady progress over arrogant self-confidence and demonstrates the destructive power of arrogance and the salvific potential of perseverance.

The tortoise wins not because of natural gifts, but because of steadfastness. The same spirit is found in Christ’s words: “Whoever humbles himself will be exalted.” “He who endures to the end will be saved” (Matthew 24:13).

Saint Basil the Great emphasizes that spiritual progress is not the result of speed or spectacular actions, but of steady ascetic practice and patience in the struggle for virtue: “The achievements of virtue are not accomplished in haste, but in time and patience.” (Very Detailed Rules (Όροι κατὰ πλάτος), Question 22, PG 31, 1017)

Liturgically, the Church cultivates the same virtue through repetition and the ascetical rhythm of the ecclesiastical year.

The Christian life is not a contest of display, but a long journey of ascetic effort. The fable thus functions as a natural foreshadowing of the spiritual path.

b) The Wolf and the Lamb – Injustice and Innocence

The fable exposes the mechanism of violence disguised in pseudo-rational justification and highlights the injustice of power and the abuse of authority. The strong fabricate causes to justify injustice. The wolf invents false accusations to legitimize his violence. This is an image of fallen human authority.

The Old Testament speaks of Christ: “Like a lamb before its shearer is silent” (Isaiah 53:7).

Saint Gregory the Theologian writes that the fable depicts a world without redemption, while the Gospel reveals redemption through sacrifice, interpreting Christ’s silence as a free act of love (Oration XLV, PG 36, 632).

The hymnography of Holy Week transforms this silence into ecclesial experience.

This image directly refers to Christ as the “blameless Lamb,” who endured unjust judgment without retaliation.

Saint Gregory the Theologian emphasizes that God’s true power is revealed not in violence, but in voluntary sacrifice and love: “He was led as a silent lamb, not as one powerless, but as one willing.” “He is wronged and remains silent, in order to heal our injustice” (Oration XLV, On Pascha, PG 36, 632).

The Church sees in the fable a tragic image of the world without Christ, while in the Gospel the victory of innocence is revealed through the Resurrection.

c) The Fox and the Grapes – Self-Deception and Spiritual Blindness

The fable reveals humanity’s tendency to turn failure into contempt in order to protect ego. This mechanism is deeply spiritual.

The fable vividly describes the mechanism of self-justification and hypocrisy. The fox devalues what it cannot obtain.

When a person cannot attain something, they disparage it. This attitude stands in opposition to Christian sincerity and repentance. The Fathers of the Church repeatedly warn against spiritual delusion—human attempts to justify passions instead of healing them: “If we say that we have no sin, we deceive ourselves” (1 John 1:8).

Saint Maximus the Confessor analyzes self-love as the root of this delusion: “When the mind cannot acquire virtue, it invents justifications for the passions.” “Self-love gives birth to delusion, and delusion justifies the passions” (Chapters on Love, II, 8, PG 90, 964).

Liturgically, the spirit of self-accusation is expressed in the Prayer of Saint Ephrem the Syrian: “Yes, Lord and King, grant me to see my own transgressions…”

The liturgical life, especially during Great Lent, systematically dismantles this delusion through prayer and self-reproach.

The fable reveals a psychological mechanism; the Church reveals healing through repentance. Patristic thought deepens the fable, showing that self-deception is not merely a moral flaw, but an obstacle to salvation.

d) The Cicada and the Ant – Providence, Work, and Spiritual Watchfulness

The cicada lives in the present without concern for the future. Its negligence leads to impasse. The fable teaches responsibility and foresight, addressing accountability toward time.

Apostle Paul connects work with responsibility: “If anyone is unwilling to work, let him not eat” (2 Thessalonians 3:10).

Saint John Chrysostom teaches that work is a means of pedagogy, not merely subsistence. He links work with spiritual vigilance: “Not work alone, but a provident disposition saves a person” (On 2nd Thessalonians, PG 62, 485).

The hymnography of Great Lent calls for vigilance: “My soul, my soul, arise; why are you sleeping?” (Great Canon of Saint Andrew of Crete).

The fable functions as a call to spiritual watchfulness; the present prepares eternity.

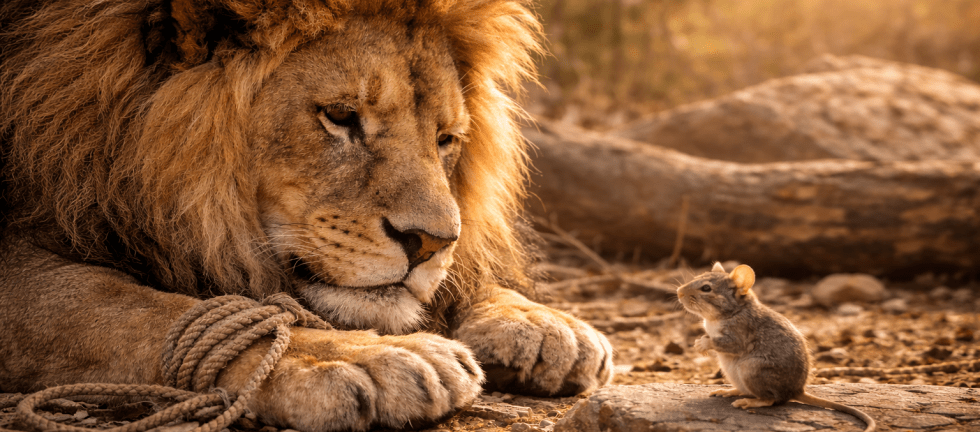

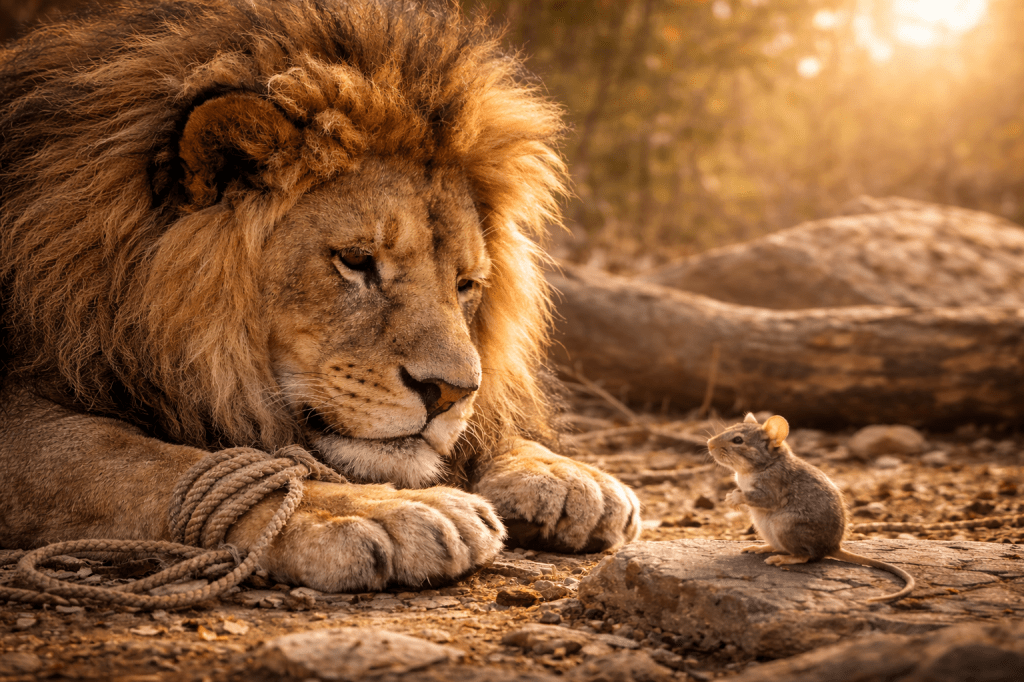

e) The Lion and the Mouse – Mercy and Humility

The small mouse saves the mighty lion. The fable overturns the worldly concept of power: the small saves the great.

Holy Scripture proclaims that grace is given to the humble: “God gives grace to the humble” (James 4:6).

Saint Basil the Great emphasizes that true power is not a natural magnitude but a gift of God: “Power lies not in size, but in the grace of God” (Homily on Humility, PG 31, 529).

The Orthodox Church has never categorically rejected pre-Christian thought. On the contrary, it subjected it to discernment, distinguished it, and made use of it. The Fathers saw in Aesop’s fables a preparatory discourse; a natural morality that prepares humanity to receive the light of the Gospel.

The classic Patristic formulation of this stance belongs to Saint Basil the Great, who characterizes “external education” as preparation for life in Christ: “External wisdom is a kind of preparation for the life according to Christ.”

This wisdom does not save, but prepares. It does not transform, but educates.

In his well-known address to the youth, the Saint exhorts them to gather from secular wisdom whatever leads to virtue, just as the bee takes only the nectar from the flower: “As bees take only what is useful from flowers, so we also from secular writings” (Address to the Youth, PG 31, 564).

Aesop’s fables, therefore, can be viewed as preparation: they cultivate conscience, enabling humanity to be receptive to the light of the Gospel. Thus, Aesop’s fables are not adversaries of the Gospel, but servants of its pedagogical preparation.

What Aesop suggests, Christ reveals. What natural morality teaches, the Church transforms into a path of salvation. The Church unites the two, leading humanity from knowledge to deification.

Natural morality is not abolished, but finds its fulfillment in Christ, where the word becomes life and teaching is transformed into salvation.

Aesop’s fables do not save; they teach. The Gospel does not merely teach; it transforms. Thus, Aesop speaks to conscience, Christ speaks to the heart, and the Church leads the whole human person to salvation and deification.

The fables of Aesop and the teaching of Christ meet at the level of moral formation and the cultivation of human ethos. The fables show the path of natural virtue; the Gospel reveals the path of salvation. The Fathers of the Church bridge these two worlds, showing us that every true teaching finds its completion in the light of Christ.