Του Σεβ. Μητροπολίτου Σουηδίας κ. Κλεόπα

Από την αρχαιότητα μέχρι σήμερα, ο άνθρωπος αναζητά τρόπους να εκφράσει την αλήθεια, να διδάξει την αρετή και να καταδείξει τις συνέπειες της ανθρώπινης συμπεριφοράς.

Δύο μεγάλα παιδαγωγικά ρεύματα της ιστορίας, φαινομενικά διαφορετικά, αλλά ουσιαστικά συγκλίνοντα, είναι οι μύθοι του Αισώπου και η διδασκαλία του Χριστού, όπως αυτή ερμηνεύεται και βιώνεται μέσα στην Ορθόδοξη Παράδοση.

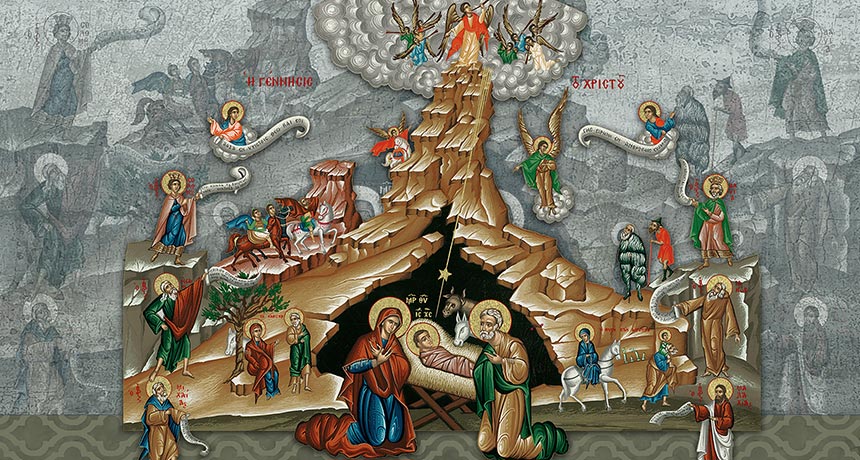

Η πορεία του ανθρώπου προς την αλήθεια δεν υπήρξε ποτέ στιγμιαία· υπήρξε σταδιακή, παιδαγωγική και αποκαλυπτική. Πριν ακόμη ακουστεί ο λόγος του Ευαγγελίου, ο άνθρωπος είχε ήδη λάβει σπέρματα αλήθειας μέσω της συνείδησης, της εμπειρίας και της παρατήρησης του κόσμου.

Σε αυτή τη διαδικασία εντάσσονται οι μύθοι του Αισώπου, οι οποίοι, αν και στερούνται αποκαλυπτικού χαρακτήρα, αποτυπώνουν με ενάργεια τη φυσική ηθική τάξη.

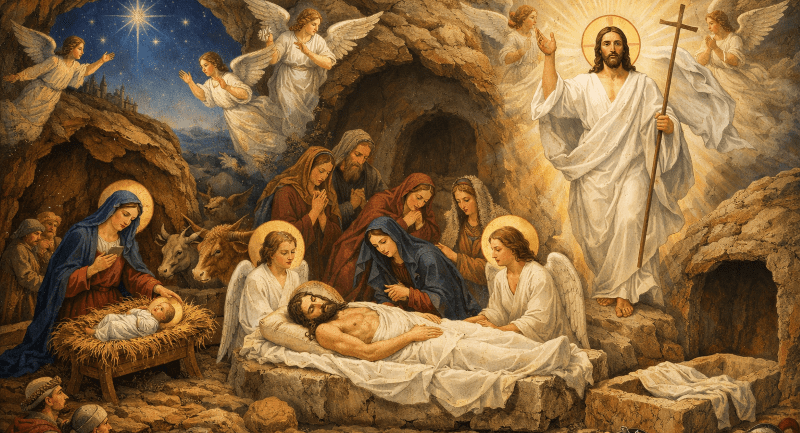

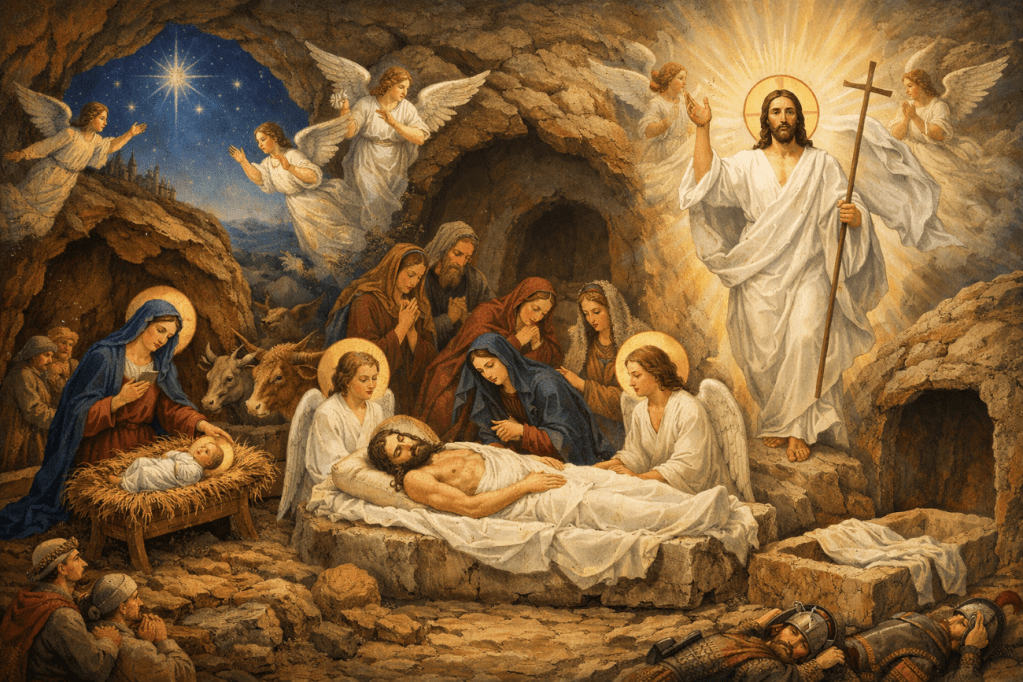

Με τον ερχομό του Χριστού, η ηθική αυτή γνώση δεν αναιρείται αλλά υπερβαίνεται και οδηγείται στην πληρότητά της.

Οι Πατέρες της Εκκλησίας, με διάκριση και σοφία, αναγνώρισαν στους μύθους αυτούς μια προπαιδεία του Ευαγγελίου, έναν προθάλαμο που προετοιμάζει τον άνθρωπο για την αλήθεια της σωτηρίας.

Η ανθρώπινη ιστορία της παιδείας δεν αρχίζει ούτε τελειώνει με τον Χριστιανισμό, αλλά στον Χριστιανισμό βρίσκει την πληρότητα και τη σωτηριολογική της ολοκλήρωση.

Πριν από το Ευαγγέλιο, ο άνθρωπος διδάχθηκε μέσω της εμπειρίας, της φιλοσοφίας και του μύθου. Ένας από τους σημαντικότερους φορείς αυτής της ηθικής προπαιδείας υπήρξε ο Αίσωπος, του οποίου οι μύθοι, με απλό αλλά διεισδυτικό τρόπο, ανέδειξαν διαχρονικές αλήθειες για την ανθρώπινη φύση.

Οι μύθοι του Αισώπου χρησιμοποιούν απλές εικόνες, ζώα και καθημερινές καταστάσεις, για να μεταδώσουν βαθιά ηθικά διδάγματα. Με παρόμοιο τρόπο, ο Χριστός μίλησε στον λαό με παραβολές: τον σπορέα, τον άσωτο υιό, τον καλό Σαμαρείτη. Και στις δύο περιπτώσεις, η αλήθεια δεν επιβάλλεται· αποκαλύπτεται στον ακροατή, που είναι έτοιμος να στοχαστεί.

Όπως σημειώνει ο Άγιος Ιωάννης ο Χρυσόστομος, η παραβολή κατεβάζει τα υψηλά νοήματα στο μέτρο της ανθρώπινης αδυναμίας, ώστε η διδασκαλία να γίνει κατανοητή και βιωματική: «Διὰ τῶν παραβολῶν παιδαγωγεῖ, ἵνα μὴ βίᾳ, ἀλλὰ προαιρέσει δέξωνται τὴν ἀλήθειαν». (Εἰς τὸ Κατὰ Ματθαῖον, Ομιλία ΜΕ΄, PG 57, 464)

Η ίδια παιδαγωγική λογική διακρίνεται και στους μύθους, οι οποίοι λειτουργούν ως καθρέπτης της ανθρώπινης συμπεριφοράς.

Όταν ήρθε ο Χριστός «ἐν πληρώματι χρόνου», δεν κατήργησε τη φυσική ηθική γνώση, αλλά την υπερέβη και την τελείωσε, οδηγώντας την από το επίπεδο της συμπεριφοράς στο επίπεδο της σωτηρίας και της κοινωνίας με τον Θεό.

Οι μύθοι του Αισώπου λειτουργούν παιδαγωγικά. Παρουσιάζουν συμπυκνωμένες αφηγήσεις, με συμβολικά πρόσωπα, που καταλήγουν σε σαφές ηθικό συμπέρασμα. Λειτουργούν ως καθρέπτης της ανθρώπινης συμπεριφοράς, προκαλώντας αυτογνωσία.

Αντίστοιχα, ο Χριστός χρησιμοποίησε τις παραβολές ως μέσο αποκαλύψεως της Βασιλείας του Θεού.

Ο Ιερός Χρυσόστομος, ερμηνεύοντας τις παραβολές, επισημαίνει: «Οὐ γὰρ διὰ σκοτεινότητα λέγει παραβολάς, ἀλλὰ διὰ συγκατάβασιν, ἵνα ἐκ τῶν αἰσθητῶν ἐπὶ τὰ νοητὰ ἀνάγῃ». (Εἰς τὸ Κατὰ Ματθαῖον, Ομιλία ΜΕ΄, PG 57, 464)

Η Εκκλησία αναγνωρίζει ότι η εικόνα και το παράδειγμα είναι απαραίτητα για τη μετάδοση της αλήθειας, ιδίως σε έναν κόσμο πνευματικά ανώριμο. Επομένως, οι μύθοι του Αισώπου εξετάζονται ως προπαιδεία του Ευαγγελίου και η ερμηνεία τους υπό το φως των Πατέρων της Ορθοδόξου κατ᾽ Ανατολάς Εκκλησίας.

Μύθος και παραβολή ως παιδαγωγικές μορφές λόγου

Παραδείγματα μύθων και θεολογικών αντιστοιχιών

Ο μύθος, όπως και η παραβολή, λειτουργεί ως έμμεσος λόγος. Δεν επιβάλλει την αλήθεια, αλλά την υπαινίσσεται. Η παραβολική διδασκαλία του Χριστού εντάσσεται ακριβώς σε αυτή την παιδαγωγική λογική.

Ο Άγιος Ιωάννης ο Χρυσόστομος επισημαίνει ότι οι παραβολές δεν αποσκοπούν στη σκίαση της αλήθειας, αλλά στη συγκατάβαση προς την ανθρώπινη αδυναμία. (Εἰς τὸ Κατὰ Ματθαῖον, Ομιλ. ΜΕ΄, PG 57, 464)

Ο άνθρωπος καλείται να αναγνωρίσει τον εαυτό του μέσα στην αφήγηση. Το ίδιο συμβαίνει και με τους μύθους του Αισώπου, οι οποίοι καθιστούν τον ακροατή κριτή και συγχρόνως κατηγορούμενο της ίδιας του της συμπεριφοράς.

α) Ο Λαγός και η Χελώνα – Υπομονή και ταπείνωση

Ο μύθος προβάλλει την υπεροχή της σταθερής πορείας έναντι της αλαζονικής αυτοπεποίθησης, καταδεικνύει δε την καταστροφική δύναμη της αλαζονείας και τη σωτήρια δυναμική της επιμονής.

Η χελώνα νικά, όχι λόγω φυσικών χαρισμάτων, αλλά λόγω σταθερότητας. Το ίδιο πνεύμα συναντούμε στον λόγο του Χριστού: «ὁ ταπεινῶν ἑαυτόν ὑψωθήσεται». «Ὁ δὲ ὑπομείνας εἰς τέλος, οὗτος σωθήσεται». (Ματθ. 24,13)

Ο Μέγας Βασίλειος τονίζει ότι η πνευματική πρόοδος δεν είναι αποτέλεσμα ταχύτητας ή εντυπωσιακών πράξεων, αλλά σταθερής άσκησης και υπομονής στον αγώνα της αρετής: «Οὐκ ἐν τάχει τὰ τῆς ἀρετῆς κατορθώματα, ἀλλ’ ἐν χρόνῳ καὶ ὑπομονῇ». «Ἡ ἀρετὴ χρόνῳ τελειοῦται, οὐκ ἐξ ὀρμῆς». (Όροι κατὰ πλάτος, Ερώτησις ΚΒ΄, PG 31, 1017)

Λειτουργικά, η Εκκλησία καλλιεργεί την ίδια αρετή μέσα από την επαναληπτικότητα και τον ασκητικό ρυθμό του εκκλησιαστικού έτους.

Η χριστιανική ζωή δεν είναι αγώνας εντυπωσιασμού, αλλά μακρά πορεία ασκήσεως. Ο μύθος λειτουργεί εδώ ως φυσική προεικόνιση της πνευματικής οδού.

β) Ο Λύκος και το Αρνί – Αδικία και αθωότητα

Ο μύθος αποκαλύπτει τον μηχανισμό της βίας που ντύνεται με ψευδολογική δικαιολογία και προβάλλεται η αδικία της ισχύος και η κατάχρηση εξουσίας. Ο ισχυρός κατασκευάζει αιτίες για να δικαιολογήσει την αδικία. Ο λύκος κατασκευάζει ψευδείς κατηγορίες για να δικαιολογήσει τη βία του. Πρόκειται για εικόνα της πεπτωκυίας ανθρώπινης εξουσίας.

Η Παλαιά Διαθήκη αναφέρει για τον Χριστό: «Ὡς ἀμνὸς ἐναντίον τοῦ κείροντος αὐτὸν ἄφωνος». (Ἠσαΐας 53,7)

Ο Άγιος Γρηγόριος ο Θεολόγος γράφει ότι ο μύθος δείχνει τον κόσμο χωρίς λύτρωση· το Ευαγγέλιο αποκαλύπτει τη λύτρωση διά της θυσίας, ερμηνεύει δε τη σιωπή του Χριστού ως ελεύθερη πράξη αγάπης. (Λόγος ΜΕ΄, PG 36, 632)

Η υμνογραφία της Μεγάλης Εβδομάδος μετατρέπει αυτή τη σιωπή σε εκκλησιαστικό βίωμα.

Η εικόνα αυτή μας παραπέμπει ευθέως στον Χριστό ως «ἀμνὸν ἄμωμον», που υπέμεινε άδικη κρίση, χωρίς να ανταποδώσει το κακό.

Ο Άγιος Γρηγόριος ο Θεολόγος επισημαίνει ότι η αληθινή δύναμη του Θεού φανερώνεται, όχι στη βία, αλλά στην εκούσια θυσία και την αγάπη: «Ὡς ἀμνὸς σιωπῶν ἤγετο, οὐχ ὡς ἀσθενής, ἀλλ’ ὡς ἐθελῶν». «Ἀδικεῖται καὶ σιωπᾷ, ἵνα τὴν ἀδικίαν ἡμῶν θεραπεύσῃ». (Λόγος ΜΕ΄, Εἰς τὸ Πάσχα, PG 36, 632)

Η Εκκλησία βλέπει στον μύθο μια τραγική εικόνα του κόσμου χωρίς Χριστό, ενώ στο Ευαγγέλιο αποκαλύπτεται η νίκη της αθωότητας διά της Αναστάσεως.

γ) Η Αλεπού και τα Σταφύλια – Αυταπάτη και πνευματική τύφλωση

Ο μύθος φανερώνει τη ροπή του ανθρώπου να μετατρέπει την αποτυχία σε περιφρόνηση, για να προστατεύσει τον εγωισμό του. Αυτός ο μηχανισμός είναι βαθιά πνευματικός.

Ο μύθος περιγράφει με ενάργεια τον μηχανισμό της αυτοδικαίωσης και της υποκρισίας. Η αλεπού απαξιώνει αυτό που δεν μπορεί να αποκτήσει.

Όταν ο άνθρωπος δεν μπορεί να φτάσει κάτι, το απαξιώνει. Η στάση αυτή έρχεται σε αντίθεση με τη χριστιανική ειλικρίνεια και μετάνοια. Οι Πατέρες της Εκκλησίας επανειλημμένα προειδοποιούν για την πνευματική αυταπάτη, δηλαδή την προσπάθεια του ανθρώπου να δικαιολογήσει τα πάθη του, αντί να τα θεραπεύσει. «Ἐὰν εἴπωμεν ὅτι ἁμαρτίαν οὐκ ἔχομεν, ἑαυτοὺς πλανῶμεν». (Α΄ Ἰωάννου 1,8)

Ο Άγιος Μάξιμος ο Ομολογητής αναλύει τη φιλαυτία ως ρίζα αυτής της πλάνης: «Ὁ νοῦς, ὅταν μὴ δύνηται τὴν ἀρετὴν κτήσασθαι, ἐφευρίσκει λόγους δικαιώσεως τῶν παθῶν». «Ἡ φιλαυτία γεννᾷ τὴν πλάνην, καὶ ἡ πλάνη δικαιοῖ τὰ πάθη». (Κεφάλαια περὶ ἀγάπης, Β΄, 8, PG 90, 964)

Λειτουργικά, το πνεύμα της αυτομεμψίας εκφράζεται στην ευχή του Αγίου Εφραίμ του Σύρου: «Ναί, Κύριε Βασιλεῦ, δώρησαί μοι τοῦ ὁρᾶν τὰ ἐμὰ πταίσματα…»

Η λειτουργική ζωή, ιδίως κατά τη Μεγάλη Τεσσαρακοστή, αποδομεί συστηματικά αυτή την αυταπάτη, μέσω της προσευχής και της αυτομεμψίας.

Ο μύθος αποκαλύπτει ψυχολογικό μηχανισμό· η Εκκλησία αποκαλύπτει θεραπεία, μέσω μετανοίας. Η Πατερική σκέψη εμβαθύνει τον μύθο, δείχνοντας ότι η αυταπάτη δεν είναι απλώς ηθικό ελάττωμα, αλλά εμπόδιο στη σωτηρία.

δ) Ο Τζίτζικας και ο Μέρμηγκας – Πρόνοια, εργασία και πνευματική εγρήγορση

Ο τζίτζικας ζει στο παρόν, χωρίς μέριμνα για το μέλλον. Η αμέλεια του τζίτζικα οδηγεί σε αδιέξοδο. Ο μύθος διδάσκει την ευθύνη και την πρόνοια, πραγματεύεται δε την ευθύνη απέναντι στον χρόνο.

Ο Απόστολος Παύλος συνδέει την εργασία με την υπευθυνότητα. Η Παύλειος διδασκαλία για την εργασία δεν έχει ηθικιστικό, αλλά παιδαγωγικό χαρακτήρα: «Ὁ μὴ θέλων ἐργάζεσθαι, μηδὲ ἐσθιέτω». (Β΄ Θεσσαλονικεῖς 3,10)

Ο Άγιος Ιωάννης ο Χρυσόστομος διδάσκει ότι η εργασία αποτελεί μέσο παιδαγωγίας και όχι απλώς βιοπορισμού. Συνδέει την εργασία με την πνευματική εγρήγορση: «Οὐχ ἡ ἐργασία μόνον, ἀλλὰ ἡ προνοητικὴ διάθεσις σώζει τὸν ἄνθρωπον». (Εἰς Β΄ Θεσσαλονικεῖς, PG 62, 485)

Η υμνογραφία της Μεγάλης Τεσσαρακοστής καλεί σε εγρήγορση: «Ψυχή μου, ψυχή μου, ἀνάστα, τί καθεύδεις;» (Μεγάλος Κανών Αγίου Ανδρέου Κρήτης)

Ο μύθος λειτουργεί ως κάλεσμα για πνευματική εγρήγορση. Το παρόν προετοιμάζει την αιωνιότητα.

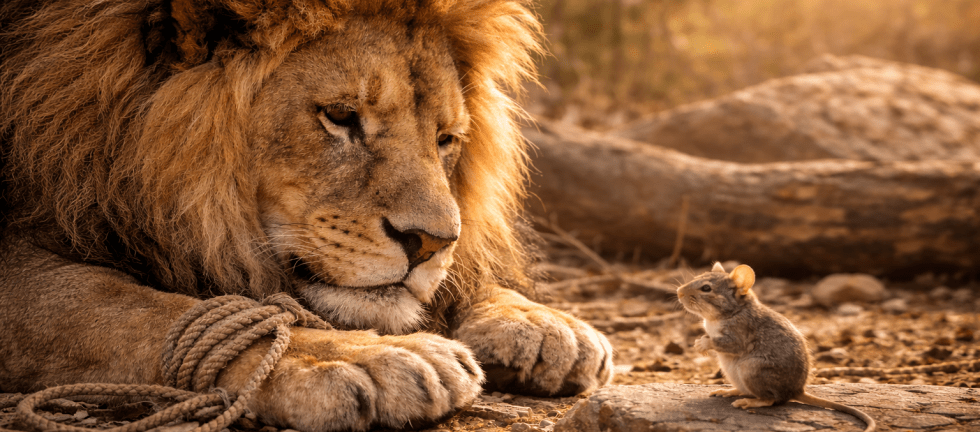

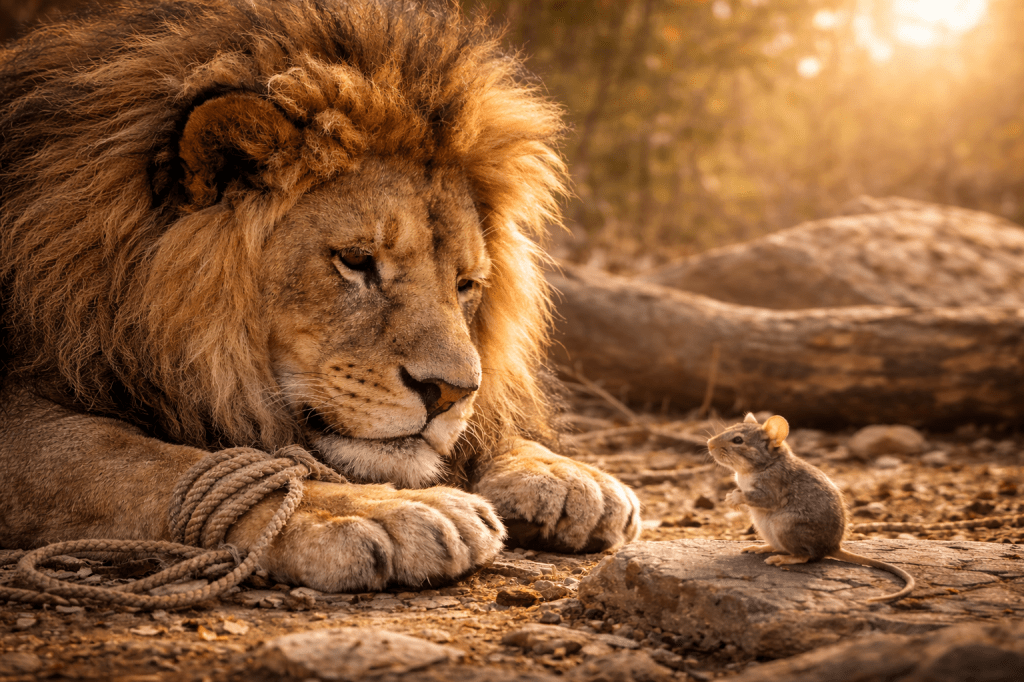

ε) Το Λιοντάρι και το Ποντίκι – Έλεος και ταπείνωση

Το μικρό ποντίκι σώζει το ισχυρό λιοντάρι. Ο μύθος ανατρέπει την κοσμική αντίληψη περί ισχύος. Ο μικρός σώζει τον μεγάλο.

Η Αγία Γραφή διακηρύσσει ότι η χάρις δίδεται στους ταπεινούς: «Ὁ Θεὸς τοῖς ταπεινοῖς δίδωσι χάριν». (Ἰακώβου 4,6)

Ο Μέγας Βασίλειος υπογραμμίζει ότι η αληθινή δύναμη δεν είναι φυσικό μέγεθος, αλλά δωρεά του Θεού: «Οὐκ ἐν τῷ μεγέθει ἡ δύναμις, ἀλλ’ ἐν τῇ χάριτι τοῦ Θεοῦ». (Ομιλία εἰς τὴν ταπείνωσιν, PG 31, 529)

Η Ορθόδοξη Εκκλησία ουδέποτε απέρριψε συλλήβδην την προχριστιανική σκέψη. Αντιθέτως, την υπέταξε σε διάκριση. Τη διέκρινε και την αξιοποίησε. Οι Πατέρες είδαν στους μύθους του Αισώπου έναν προπαιδευτικό λόγο, μια φυσική ηθική που προετοιμάζει τον άνθρωπο να δεχθεί το φως του Ευαγγελίου.

Η κλασική διατύπωση της Πατερικής στάσης απέναντι στην αρχαία σοφία ανήκει στον Μέγα Βασίλειο, ο οποίος χαρακτηρίζει την «ἔξω παιδεία» ως προπαιδεία προς την εν Χριστώ ζωή: «Προπαιδεία τις ἐστὶν ἡ ἔξω σοφία πρὸς τὴν κατὰ Χριστὸν ζωήν». Η σοφία αυτή δεν σώζει, αλλά προετοιμάζει. Δεν μεταμορφώνει, αλλά παιδαγωγεί.

Στο γνωστό του κείμενο προς τους νέους, ο Άγιος προτρέπει να συλλέγουμε από την κοσμική σοφία ό,τι οδηγεί στην αρετή, όπως η μέλισσα παίρνει από το άνθος μόνο το νέκταρ: «Ὥσπερ αἱ μέλισσαι ἐκ τῶν ἀνθέων τὸ χρήσιμον μόνον λαμβάνουσιν, οὕτω καὶ ἡμεῖς ἐκ τῶν ἔξω λόγων». (Πρὸς τοὺς νέους, PG 31, 564)

Οι μύθοι του Αισώπου, επομένως, μπορούν να ιδωθούν ως προπαιδεία: καλλιεργούν τη συνείδηση, ώστε ο άνθρωπος να είναι δεκτικός στο φως του Ευαγγελίου. Οι μύθοι του Αισώπου, επομένως, δεν είναι αντίπαλοι του Ευαγγελίου, αλλά υπηρέτες της παιδαγωγικής του προετοιμασίας.

Ό,τι ο Αίσωπος υπαινίσσεται, ο Χριστός αποκαλύπτει. Ό,τι η φυσική ηθική διδάσκει, η Εκκλησία το μεταμορφώνει σε οδό σωτηρίας. Η Εκκλησία ενώνει τα δύο, οδηγώντας τον άνθρωπο από τη γνώση στη θέωση.

Η φυσική ηθική δεν καταργείται, αλλά βρίσκει το πλήρωμά της εν Χριστώ, όπου ο λόγος γίνεται ζωή και η διδασκαλία μεταμορφώνεται σε σωτηρία.

Οι μύθοι του Αισώπου δεν σώζουν· διδάσκουν. Το Ευαγγέλιο δεν διδάσκει απλώς· μεταμορφώνει. Έτσι, ο Αίσωπος μιλά στη συνείδηση, ο Χριστός μιλά στην καρδιά, και η Εκκλησία οδηγεί ολόκληρο τον άνθρωπο στη σωτηρία και τη θέωση.

Οι μύθοι του Αισώπου και η διδασκαλία του Χριστού συναντώνται στο επίπεδο της ηθικής αγωγής και της καλλιέργειας του ανθρώπινου ήθους. Οι μύθοι δείχνουν τον δρόμο της φυσικής αρετής· το Ευαγγέλιο αποκαλύπτει τον δρόμο της σωτηρίας. Οι Πατέρες της Εκκλησίας γεφυρώνουν αυτούς τους δύο κόσμους, δείχνοντάς μας ότι κάθε αληθινό δίδαγμα βρίσκει την τελείωσή του μέσα στο φως του Χριστού.